The Payoff Pitch

The List

The List

Here is The List, a compilation of names intended to serve as a more egalitarian and apolitical response to the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown....

Monday, 19 June 2023

The List

Saturday, 16 July 2022

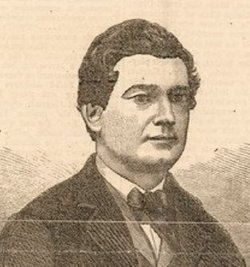

Class of 1887, 2/2 : Octavius Catto

Octavius V Catto (1839-1871), Builder

Eligible : 1872

Contributions : An important civil rights activist in the Philadelphia area, Catto helped found the Pythian Base Ball Club, one of the earliest known black baseball clubs and a precursor to the Negro Leagues. Challenged the baseball establishment by applying to the NABBP in 1867, and effectively laid the foundation for the colour barrier when the Pythian was rejected.Everybody knows the story of how the colour barrier was broken in baseball, allowing black players, and eventually players of all ethnicities, to play professional baseball : in 1947 Jackie Robinson was called up to the LA Dodgers, and endured years of vile epithets and jeers in stadiums across the country, beanballs, criticism from the press, umpires, opposing players and teammates alike, kept his head high and put in a Hall of Fame career, paving the way for many of the best players of the second half of the 20th century. Of course, this narrative is false. Not the stuff that happened to Jackie, or the things Jackie did. But the idea that Jackie Robinson broke baseball's colour barrier in April 1947 is wrong.

Fans of baseball history will know that on 1 May, 1884 Moses Fleetwood Walker, a black man from Mount Pleasant, Ohio, caught his first game for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association (AA), one of two major leagues at the time, making him the first black man to play professional baseball before being run out of the game later that year by significant racial pressure. But this, too is wrong. Again, all of these things happened, but Walker was not the first.

In June of 1879 William E White, a freed slave, played for the Providence Greys. He wasn't great and was out of baseball later that year, and his story is complicated by his status as what was then known as a 'mulatto', the son of his slave mother and his owner father. His mixed race allowed him to hide his identity as a black man for much of his life. Is White the first professional black baseball player? If not, who is?

It's complicated.

The issue of black people playing baseball is an important one, and its history is as old as baseball itself. I would respectfully suggest we remove some of the emphasis placed on Jackie, or Fleetwood, or White. While they certainly deserve the respect they each earned in their own rights, to reduce not just their own stories but the story of black men in baseball to a single game in the spring of 1947 or 1884 serves chiefly to erase so much of important black baseball history -- not just the negro leagues, for which there is significant political will to revive and maintain their history, but the half-century of baseball that predates even the earliest official negro leagues, back to the very beginning of baseball in the Northeastern United States as we know it.

This is not the story of the beginning of black baseball, but its the story of a man who was as close to such a thing as can be credited to a distinguishable character. This is the story of Octavius V Catto.

Catto was born in Charleston, South Carolina on 22 February, 1839, to a free-born mother and a father who had been granted his freedom after a life of slavery as a millwright. Catto's mother, Sarah Isabella Cain, was a prominent Charleston socialite and activist within the black community, and his father, William, became an ordained Presbyterian minister before relocating his family to the north - first Baltimore, then Philadelphia, in the free state of Pennsylvania.

As the son of prominent members of the black community, Catto received a diverse education, including segregated primary schools, the all-white Allentown Academy in New Jersey, and the Institute for Coloured Youth (ICY), the country's first and most prestigious all-black high school where he received a top-rate classical education in literature, Latin, Greek, and Mathematics. While at ICY Catto joined a scholarship discussion group led by Jacob C White, whom we may hear from again in these pages. After graduating in 1858, Catto continued learning Greek and Latin with a private tutor in Washington, DC.

In 1859 Catto returned to the staff at ICY, now named the Benneker Institute, as Recording Secretary and a teacher of English and mathematics. By the mid-1860s Catto was a leader among the staff, and gave the commencement address for 1864, during which he criticised white teachers of black students, and commented on the developing Civil War. By the following year he was speaking to packed houses at Philadelphia's National Hall, and by 1869 he was principal of male students at Benneker.

|

| Catto as a recruiter in the Civil War |

Through the 1860s Catto fought hard to desegregate Philadelphia's trolley car system, and was involved in at least one early instance of civil disobedience, which the New York Times reported :

Philadelphia, Wednesday, May 17—2 P. M.

Last evening a colored man got into a Pine-street passenger car, and refused all entreaties to leave the car, where his presence appeared to be not desired.

The conductor of the car, fearful of being fined for ejecting him, as was done by the Judges of one of our courts in a similar case, ran the car off the track, detached the horses, and left the colored man to occupy the car all by himself.

The colored man still firmly maintains his position in the car, having spent the whole of the night there.

The conductor looks upon the part he enacted in the affair as a splendid piece of strategy.

The matter creates quite a sensation in the neighborhood where the car is standing, and crowds of sympathizers flock around the colored man.

— New York Times, May 18, 1865, p. 5

Catto's advocacy paid off when, with the help of legendary congressman and abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens, Pennsylvania abolished the practice of segregated public transportation in 1869.

|

| 1863 Pamphlet citing Catto's speeches |

Catto's relevance to our Hall and to baseball history started in his youth. As a young man at various institutions of higher learning, Catto played cricket, like so many young men, both black and white. At some point in their teenage years Catto and one of his close friends, Jacob C White, switched to baseball and while teaching at the ICY founded a baseball team - the Independent Base Ball Club - in the mid-1860s.

Catto and White had a greater vision for the Independent than a casual / hobbyist squad for young professional men like the New York clubs 20 years earlier. To them, fielding a competitive team representing a black institution of higher learning was an important statement for civil rights, and in the fallout of the Civil War (ending 1865), baseball was one of the most important arenas of American cultural life, and making a statement there was incredibly significant. By 1866 the Independent was one of the best teams in the city, and renamed themselves after one of the ICY's more popular fraternities, the Knights of Pythias - the Pythians.

Catto was the the driving force behind the club - co-founder, captain, and starting shortstop/second baseman. While the team was very successful, going 9-1 in 1866 and undefeated in 1868, the impact on the larger black community was significant. The Pythian were one of the most famous black clubs in the northeast, and their matches against black clubs from Washington drew huge crowds. When the Pythian played the Washington Alert, founded by Frederick Douglass, jr., Frederick Douglass himself came to watch. These games between elite black clubs were covered favourably in the press, and attended and promoted by white players. Catto had been right - black baseball was an avenue to positive sentiment from the white class, and pride for the black community.

Catto's leadership and fine play led the team to an undefeated 1868 season. Catto's plan worked magnificently - the Pythians were famed not just or their skill on the field (particularly with the bat) but for being gentlemanly and upstanding young men, and garnered positive reviews from onlookers and journalists alike. It should be noted that this patronizing language could be taken as offense, and maybe should be, but it was exactly what Catto was after. His goal was not just to put a winning black ballclub on the field, but to display a winning and mature black disposition to a white audience.

The Pythian was a political home run for Catto, as atrocious as the pun is. It gave him an opportunity to address and organize huge crowds of young black men. He would often give speeches before or after games to the gathered crowds (again, of both black and white spectators) on issues of civil rights, and he took the Pythian around the Northeast and down the Atlantic coast in an early example of barnstorming's illustrious history in baseball, speaking to crowds the entire way. Baseball was exactly the civil rights vehicle Catto had hoped.

The Pythian's success saw enormous effects on the Philadelphia baseball community. In the wake of the Pythian's success, many black clubs organized overnight, including several women's clubs, which drew large crowds. When Philadelphia emerged as a hub of Negro League baseball in the coming decades, it was thanks to Philly's history as a hub of black baseball, and that reputation can trace its lineage directly to Catto and the Pythian. In fact Philly owes much of its reputation as a baseball town to its history as a black baseball town, and has, again, Octavius V Catto to thank for that fact.

I shouldn't imply that Catto's career with the Pythians was comprised of never ending successes; there were limitations to what the white establishment, in government or in organized baseball, would allow. For example, Catto's 1867 petition to have the Pythians admitted to the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) is an important moment in baseball history. Following that season of play, Catto applied to be admitted to the Pennsylvania State Association of Base Ball Players, the state chapter of the NABBP, with the support of the member Philadelphia Athletic club, the renowned club that was the precursor and namesake of today's Oakland A's.

The Athletics, a respected club of the amateur era, were run by player / manager Hicks Hayhurst, who seemed energized by the pre-Jim Crow era of reconciliation and would regularly stage games between his white club and area black clubs to highlight the skill of the latter, and was happy to sponsor the Pythian to the Pennsylvania Association. For all Catto had done to further the cause of black baseball and civil rights, the 1867 convention was a harsh lesson : the Pythian were not only rejected, but denied the chance to address the convention or request a vote on their membership, while the convention admitted 265 new white teams.

Catto, never one to be deterred, attended the national convention of the NABBP in Philadelphia later that year, submitting another application for membership to the national body and again supported by the Athletics. This time the proposal was allowed to see the floor as a vote, but the result was the same : there would be no black baseball team in the NABBP. The National Association explained their verdict in an almost benevolent, regretful tone : "If Colored clubs were admitted there would be, in all probability, some division of feeling, whereas by excluding them no injury would result to anyone." Later statements confirmed an aversion to 'politics' in what would amount to an abdication of responsibility in the discussion, and one that was later apologised for by baseball historians, who wrote of baseball as a 'healing balm' between north and south, which was too important to be hampered by the inclusion of blacks, showing that baseball's distasteful colour barrier dates back essentially to the invention of the game.

Catto, again, changed tack. Realising that he would never be invited or allowed to participate in what was evidently a white man's organization, he endeavored to use baseball for his civil cause in a new way - by beating a white club. In an inversion of the old axiom, if Catto couldn't join 'em, he would simply beat 'em.

Initially it seemed like the Pythians would have a hard time finding a dance partner - what white club would risk the humiliation of losing to a black one? But again, Catto had an ally in the Philadelphia Athletic. One of the Athletic's founders, Thomas Fitzgerald, was a stanch progressive on race and had one of the loudest megaphones in the city as the publisher of City Item. He regularly published pieces arguing for black voting rights, to the point that his views were considered too radical for the Athletic and he was ousted from the club. Fitzgerald spent much of 1869 arguing for normalizing relations between black and white baseball. He called out the Athletic in particular, arguing that they were afraid of losing to the black Pythian, and public pressure mounted.

By August of 1869 white clubs were lining up to express interest in Philadelphia papers in playing the Pythian - first the Masonics, then the Keystones, the Experts, the Franklins, even the Athletics. But it was just publicity - no games between white and black players took place. Still, Fitzgerald beat the drum in the press and Catto leveraged his political and commercial relationships. Soon the Philadelphia Olympic, by many accounts the nation's oldest ballclub with roots dating to 1831, accepted, and the two clubs took the field on 3 September 1869, the first interracial game, at least of this profile, in baseball history. The game took place on the Olympic's home field, and Fitzgerald served as the umpire.

The game drew an immense crowd - by some accounts the largest crowd in the history of baseball outside of the Olympic's game against the legendary Cincinnati Red Stockings earlier that summer. It was another example of Catto's view of baseball as a vehicle for demonstrating the qualities of African Americans. At the time, the game had one umpire who instead of calling every safe/out, would adjudicate as players called their own outs, in case of a dispute. Before the game Catto instructed his players not to appeal any call by the Olympic, as they would be viewed as blacks complaining to whites in front of a high-profile crowd of thousands. The Pythian, whose normal starting pitcher, John Cannon, was injured and didn't perform well. The Olympic won, 44-23, but the next day's papers praised their effort and conduct, and claimed they would have been able to win the game if they'd appealed several unfair calls to the sympathetic umpire. It was yet another PR coup for Catto and the Pythian.

Catto still wanted a victory of a white club, and got one on October 16 of the same year when the Pythian beat the City Item Club 27-17. Interracial games featuring many other black clubs became, if not common, then regular occurrences following 1869, giving a rare opportunity to workers of both races to interact with each other.

These inter-racial games would mark the highwater mark for Catto's baseball career during his lifetime, though his political activity never would end, right up to the moment of his death.

By 10 October, 1871, Election Day, Catto was a well-known political agitator, organiser, orator, writer, and teacher. Then, as now, these activities made him a hero to many - but a target to others.

On that day in 1871 Philadelphia was a tinderbox. Predominantly-Republican black people and predominantly-Democratic Irish, who called neighbouring districts home, clashed in the streets all day. Police were called on to stem the violence, but many of them were Irish themselves and were noted for inciting violence, blocking black people from voting, in some cases resulting with the arrests of the officers themselves.

|

| Illustration of Catto's murder |

|

| Marking the place of Catto's murder |

In 2017 Philadelphia erected it's first statue of an African-American - a 12-foot bronze statue of Octavius Catto at City Hall. At the unveiling, Philadelphia mayor Jim Kenney lamented, "How in God's name did I not know this man? He was the Dr. King and the Jackie Robinson of his day."

|

| 2017 statue in front of City Hall |

But because he was a towering figure in the history of civil rights does not mean that he is not an important figure in baseball history as well. In the years after his death his club, the Pythian, kept playing before chartering the National Colored Base Ball League, one of the first and most influential Negro Leagues, in 1887. Catto's fingerprints were all over the early days of black baseball.

Perhaps Catto's most important legacy is that of the activist athlete. In the United States the political athlete is an institution, from Jackie Robinson to Muhammad Ali to John Carlos and Tommy Smith to Colin Kaepernick. Fans often claim to yearn for the separation of sport and politics, but the politically active athlete is a crucial part of American history and culture. In baseball, in activism, and in the particular blend of the two, Octavius Catto led the way.

Tuesday, 19 April 2022

Class of 1887, 1/2 : Will White

William Henry 'Whoop-La' White (1854-1911), Player

Eligible : 1887

Contributions : Despite a turbulent career, White retired in 1886 as one of the best pitchers of all time. Famed for his curveball, White ranked consistently among the league leaders in innings pitched, complete games, and strikeouts.

|

| White in 1882 |

Will White is not somebody whose name will be shouted from the rooftops in baseball history. He won't end up in Cooperstown, and to be honest he isn't among the best players to be inducted here - but for a brief moment in the 1880s White was one of the best pitchers to ever live, and certainly the best player in baseball history eligible for our hall.

William Henry White was born in the farming community Caton, NY, in October 1854. He was the fourth of eight children and grew up playing baseball primarily with his family - his older brother James and cousin Elmer White both played in the first season of openly professional play in the National Association, 1871. James would go on to craft a legend in his own right as 'Deacon White.'

By 1875, aged 20, William seemed on the fast track to professional success. He was renowned in regional baseball circles for his curveball, and he was a star pitcher for the amateur powerhouse Lynn (Massachusetts) Live Oaks. That same year he married Harriet Holmes.

1876 and 1877 were something of lost years for White in terms of his career professional statistics. Both years he played for a top pro-am club, the Binghamton Crickets, establishing himself as one of the best pitchers in the country, yet not in the fledgling National League, the established highest league in the country. Still, as 1877 wound down his older brother James (now nationally famous as Deacon), the star catcher and '77 batting champion for the Boston Red Stockings convinced his time to give Will a tryout. Will pitched three games (with his brother, now primarily an infielder, returning to catch his younger brother) and impressed onlookers with his dazzling curveball. He completed all three games, won two of them, and put up an average 3.00 ERA.

White was also something of a sensation for wearing glasses, something incredibly rare for anybody at the time, let alone a professional baseball player. Later, contemporaries would wonder at how he managed to be one of the dominant pitchers of his age while being legally blind.

After the 1877 season the Cincinnati Reds signed both of the White brothers. Deacon continued to be one of the best players in the league, while Will instantly established himself as the league's emerging star pitcher. He finished all 52 games that he started, won 30 games, put up a 1.79 ERA (120 ERA+), and was better the next year, throwing 75 complete games (and an additional relief appearance), good for a league-leading 680 innings, winning 43 times, and posting a 1.99 ERA (120+). Over the two seasons nobody pitched more innings or had a lower ERA, and only the living legend Tommy Bond, pitching for the powerhouse Boston club won more games.

In 1879 Cincinnati newspaperman OP Caylor staged an exhibition of White's curveball, which was his calling card but had accrued an almost unbelievable reputation. The demonstration had White throw a baseball along a fence at an angle so that the ball slipped through a gap in the fence, miss a post that was in-line with the fence to the right, then curve back to the left of the fence when the fencing resumed (see diagram).

White was strong again in 1880, starting and finishing 62 games and putting up a 2.14 ERA. Unfortunately the Reds had abysmal hitting and fielding, and won just 21 games as their attendance cratered. In an attempt to increase revenue and bring more fans to the park, the Reds began selling beer during games and renting the park to amateur and semi-pro teams on Sundays. National League president William Hulbert, who founded the NL as a straight-laced alternative to the rowdy NA, demanded they cease both practices. When the Reds refused, Hulbert trounced them from the league. White was without a job.White caught on with the Detroit Wolverines, newly added to the NL, in time for the 1881 season, but pitched poorly in a two-game tryout and was released. White complained of a sore arm, but returned to Cincinnati to play casually for local semi-pro clubs.

By the end of 1881 a number of businessmen and baseball figures including the owners of the now-defunct Cincinnati club and the Cincinnati sportswriter OP Caylor, a longtime associate of White's, had laid plans for a new baseball league to compete with the National League - the American Association. The AA essentially marketed itself as a working-class alternative to the NL, offering lower ticket prices, alcohol sales, Sunday afternoon baseball, and franchises in what Hulbert had once referred to as 'river cities' - working class cities like Louisville, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati considered low-brow by Northeastern elites. The AA was an instant success, and gained traction in the press as the 'Beer and Whiskey League.'

White signed on to the rebooted Cincinnati Reds club, and picked up right where he left off. Over 1882-83 White started 119 games, finishing 116 of them. Over 1057 innings he posted a 1.84 ERA (163+). Nobody anywhere in baseball won more games during that time, and only the legendary Charles 'Old Hoss' Radbourn threw more innings. No qualified pitcher had a lower ERA. The Red Stockings cruised to the inaugural Association pennant. The Philadelphia Athletics finished second - 11.5 games back.

As one reads the biographies of 19th-century ballplayers, something jumps out at the reader - every ballplayer was a drinker, a gambler, a womanizer, except whoever one is currently reading about. The same rings true for White - as we all know, professional baseball was rife with debauchery, but White famously refused his entire career to pitch on Sundays, was baptised into the Second Adventist church in August of 1883, and when it came time to invest some of his baseball wages, invested not in a saloon but a tea house on Market Street in Cincinnati. Maybe White was a stern, sober man who eschewed the vices of his contemporaries, or maybe this is post-facto image improvement, as I suspect many such cases are. From all the evidence, though, White appears to have been a man of principle.

By 1884 White was one of the best pitchers of all time, and one of the best two or three pitchers still working. As often befitted a superstar player, Cincinnati made him club manager, though he handed over the reins halfway through the season (despite an impressive 44-27 record), claiming that he was "of too easy a disposition." Indeed, by all accounts he was too mild-mannered to effectively manage. Bespectacled from youth, grey-haired from age 28 and by the mid 1880s prematurely bald, the strait-laced White carried a "professorial" air. Others called him "timid."

1884 marked a turning point in the career of Will White. Up to that point in most baseball leagues hitting a batter would typically be ruled a ball, unless the umpire determined the pitcher had thrown at the batter on purpose. White was a master of pitching inside, intimidating batters and keeping them uncomfortable. In the only two years such statistics were kept and White pitched full-time (1884-85), he led the league in hit batters. In 1884, however, the American Association, and thereafter other leagues, changed the rules to discourage throwing at batters, awarding first base to every single hit batsman. White could no longer work inside to such an extreme degree, and his performance seemed to suffer. Not only did he give away first base all the time (62 HBP over 1884-85), but hitters were no longer constantly afraid of being beaned, and could get closer to the plate for better coverage. He pitched well enough in 1884, throwing 456 innings of league-average ball (3.32 ERA, 101+) and leading the league with 7 shutouts, but by 1885, aged 30 and complaining for years about arm and shoulder issues, White had run out of gas. He started only 34 games, going 18-15 with a below-average 3.53 ERA.

By the end of the 1885 season White knew he had nothing left in his arm. He opened a grocery store in Fairmount, Ohio, near Cincinnati, and returned in 1886 to pitch three mediocre games for the Reds, but he knew he was done and officially retired 5 July, 1886, aged 31. He immediately turned to study ophthalmy (interesting considering his status as the famous bespectacled hurler in the 1870s), opening an optical supply store with his brother Deacon in Buffalo. He also became part owner, with his brother, of the Buffalo Bisons semi-pro team, agreeing to share managerial duties and pitch for the team. When Deacon was barred from involvement in the team due to the reserve clause (his contract was still the exclusive property of the Pittsburgh Alleghanies), Will stepped in as full-time manager, and ended up pitching 20 games in 1889 for the Bisons, posting a good 2.33 ERA even at an advanced age.

White earned a reputation as a successful optician in Buffalo, but his post-baseball career was cut short when, in 1911, he suffered a heart attack and drowned while teaching his niece to swim at his summer home in Port Carling, Ontario. He was 56 years old.

White was always something of an oddity, from his famed victory shout and subsequent nickname, 'whoop-la', to his glasses, to his 'professorial manner.' He also happened to be one of the best baseball pitchers to ever live at the time of his retirement in 1886. At the time, with really just six full seasons of baseball under his belt, he ranked 5th all time in innings pitched, 12th in WAR, 6th in wins, 4th in complete games, and 3rd in shutouts. For a variety of reasons, Will White was a player for the ages.

Wednesday, 30 March 2022

Class of 1886, 2/2 : Thomas Tassie

|

| Thomas Tassie |

Friday, 10 December 2021

Class of 1886, 1/2: Tom York

Eligible: 1886

Contributions: A consistently good player, York was a solid hitter, outfielder, and baserunner from the birth of professional baseball (1871) through his retirement in 1885. He was never the best player in baseball, but he carried his success across 15 years and three pro leagues. He retired 7th all-time in runs, RBI, and wRC; 2nd in triples and 4th in doubles.

York was born in Brooklyn in 1850, and would have grown up watching the explosion of competitive baseball in New York city. In 1869, just as the Cincinnati Reds were touring the country as the first openly professional team, York joined his first affiliated club, Brooklyn's Powhatan. He played two seasons for Powhatan and earned a reputation as a hard-nosed Brooklyn ballplayer and a stellar defensive outfielder (remember at the time a player's reputation was defined by his defensive ability).

|

| York, Middle row, far right, with the 1876 Hartford Blues |

York has the pleasant post of trying to keep the actors, tonsorial artists and plumbers out of the press stand. It is old tom who examines your pink paste board and decides whether you are eligible for a seat in the press cage.

|

| York as Polo Grounds usher in 1922 |

In 1925, to celebrate 50 years of play, the NL hosted a gala in the offseason to honour the stars of NL history, but the show was stolen, allegedly, by six living men who had played in baseball's very first 'regular' season, 1871. Among them was Tom York, now 74. Interestingly, York alleged that the baseball players were more popular in his day - walking home in uniform with legions of kids following - than the stars of that time, with one exception : Babe Ruth. Ruth, York admitted, was also a better hitter than anybody he ever played with, which is the only example I can think of of an old ballplayer believing a current player was better than the ones in 'his day.'

|

| York, far left, at the 1925 National League gala |