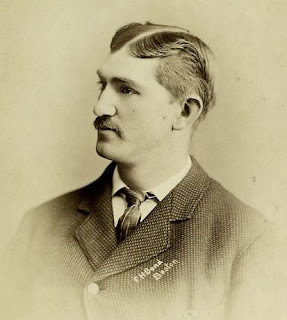

William A Hulbert (1832-1882), Builder

Eligible: 1882

Contributions: Broke from the NABBP in 1876 to found the National League. Enforced professionalism and fair play, credited with saving the young sport. President of the Chicago White Stockings until his death, one of baseball's first dynasties.

Who is the greatest Hall of Fame snub? Is it Barry Bonds or Roger Clemens? Pete Rose? Curt Schilling? Bobby Grich? For 60 years, there was only one acceptable option. In 1937, the second year of the Hall's existence, the induction committee selected for induction Ban Johnson, who founded the AL in 1901, and Morgan Bulkely, who briefly served as a puppet president of the NL in 1876. He also happened to be the first president of the NL. Satisfied that they had recognized the two most important executives in baseball history, the election committee did not revisit their selections, anointing such heroes of the sport as Tom Yawkey as the 20th century wound on. By the 1990s a debate had ignited about one of the more deserving candidates: the actual most important figure in NL history, the then-unrecognized William Hulbert. He was inducted in 1995, but we won't wait 60 years to let him in our hall.

William Ambrose Hulbert was born in the farming town of Burlington Flats, NY, in 1832, and his family moved to Chicago shortly after. He would spend much of the rest of his life there, and often professed his love for the town: "I would rather be a lamppost in Chicago than a millionaire in another city". After quickly drinking his way out of Beloit College in Wisconsin, he returned to Chicago and married Jennie Murray in 1860, and the two had a son four years later.

Hulbert could be affectionately coined an 'alcoholic', though he straightened up after his family was driven to the brink of bankruptcy and he did a stint in a Boston drying out facility. He assumed control of his family's grocery business, which he expanded into real estate, commodities trading ultimately coal mining. A lifelong fan of baseball, Hulbert bought shares in the Chicago White Stockings when they went professional for the inaugural season of National Association professional play in 1871. Led by star pitcher George Zettlein, the team fared well until their season ended when the Great Chicago Fire burned down their home, Lake Park. They did not take the field in 1872 or '73, and when they returned to play in 1874, Hulbert had become an officer of the club. He would assume the club presidency in 1875.

Outwardly, Hulbert's White Stockings operated quietly, posting a middling record in a quiet midwestern city. Behind closed doors, however, 1875 was the year that Hulbert conspired to change baseball history. There are two events cited as the reason Hulbert founded the National League, and while we don't know which was the driving force behind his decision, we know that both are true. The first is the Hulbert's snubbing in the Davy Force case:

In 1874 Force was a star infielder for Chicago, one of the best fielders in baseball who would finish 1874 with a career .346 batting average and 132 OPS+. The problem with Force was his reputation as a 'revolver', a player who showed little loyalty and jumped to the highest-paying club - moreover, Force would sign multiple contracts and leverage his suitors against each other. In the midst of 1874 Hulbert tried to get ahead of Force and sign him to a contract for 1875, which was against league rules at the time (teams had to wait until the offseason to sign players for the following season). In December, well aware of the rules, Force signed a contract with the Philadelphia Athletics. When Hulbert appealed to the Association judiciary committee, they had the Philadelphia contract annulled, but, according to legend, when a Philadelphia man was appointed to the committee, they reversed their decision and awarded Force to Philadelphia.

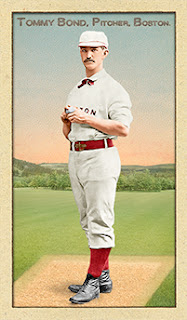

The second factor was Hulbert's jealousy. After watching players like Force revolve away from Chicago, and having to watch Boston maintain a dynasty, an opportunity fell into Hulbert's lap: a letter in July 1875 from Boston's Al Spalding, the sport's best player, offering his services as manager for the 1876 season. Hulbert raced to Boston to meet with Spalding, and returned with a contract securing his services for 1876 - as well as contracts with the rest of Boston's Big Four - Cal McVey, Ross Barnes, and Deacon White. With thoughts of a dynasty in his head, he reached out to the rest of the league's stars, and secured the services of Philadelphia's Adrian 'Cap' Anson and John Peters as well. He signed versatile veteran infielder Ezra Sutton, but he later reneged.

Hulbert was a large man, towering (for the time) at over six feet tall and, by all accounts, a force of personality, and it showed in the following events. Incensed at the injustice of the Davy Force, and afraid of association sanctions following his theft of all the association's talent for 1876, Hulbert clandestinely began sending feelers for his master plan: a new league. Hulbert had long derided, with many others, the lack of discipline in the Association. Gambling and drinking were the norm among players, and they often played inebriated, used foul language, and even played on Sundays, all of which Hulbert found not just morally atrocious (remember that he was a religiously-reformed alcoholic), but bad business in a sport that should have been reaching out to a wider family demographic. Moreover, teams had a habit of quitting the league partway through the season, especially once their home dates were played out.

Hulbert's new league would clamp down on all of this behaviour. No drinking. No gambling. No Sunday games, enforced professionalism, enforced contracts, and honored schedules. Hulbert's league would be the professional antithesis to the 'wild west' of Association play.

Rumors of Hulbert's league were a leading news story during 1875. The baseball world was concerned that Hulbert would launch his league in the midst of 1875 but all his new players finished out their contracts in Boston and Philadelphia, and the NA season concluded as planned. As the season wound down Hulbert visited the presidents of the NA's best western teams: Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Louisville and convinced them to join his National League. On February 2, 1876, he hosted the rest of the major clubs from the east: Philadelphia, Boston, Newark, and the New York Mutual, at the Grand Central hotel in Manhattan. He promised them a league with integrity, limited to cities of at least 100,000 inhabitants (later set at 75,000), where contracts would be respected, territories would be enforced, and playing schedules would be honored. The eight clubs agreed to begin play in 1876, and drew straws to elect an inaugural president. Morgan Bulkely, who served a single year, showed little interest in the league and carried out no initiatives or league business, was elected the first league president, and would go into the Hall of Fame 50 years later, despite essentially no impact on baseball history. Another theory states that Hulbert maneuvered to have Bulkely, the most respected businessman in the room, elected president to give the league credibility while the inexperienced baseball man could be largely controlled by the domineering Hulbert.

Hulbert's star-studded 1876 club went a staggering 52-14 en route to the National League's inaugural pennant, and while his club would slow in pace as Spalding, Ross, and others aged and retired, Hulbert only grew in power within the world of baseball. He slowly relinquished power over his White Stockings to his protege, Spalding, but he assumed the presidency following the 1876 season and reigned over the league with an iron fist. When New York and Philadelphia, the league's two biggest markets, failed to play out their road schedules, Hulbert expelled them. He also instituted a policy of centralised scheduling: the NL produced teams' schedules instead of the teams themselves, a practise that has endured in professional sport until today. He was also the first to hire umpires to work for the league, eliminating a serious point of bias within officiating.

The NL was innovative in other ways, too. Hulbert made a clear distinction that there were no more 'clubs' - the 'teams' were players playing ball for a salary, employees of the team owners. This gave the teams, owners, and ultimately the league significant power over the players, and Hulbert was not hesitant to wield this power.

In 1877 he banned four Louisville Grays, including star pitcher Jim Devlin, for conspiring to throw the NL pennant. The move not only provided precedent for how dirty players should be handled for the rest of baseball history, the resulting scandal saw Louisville, St. Louis, and Hartford fold. Down to just three clubs, Hulbert extended the NL into smaller markets like Indianapolis, Syracure, Milwaukee, and Providence, then in 1879 to Troy, Buffalo, and Cleveland, then Worchester and Detroit in 1880.

In 1879 news broke that the three highest-paid Cincinnati Red Stockings made more money than the rest of the team combined, and the team threatened to fold. Hulbert responded by implementing the first reserve rule, eliminating the free agent market and strongly suppressing players' wages. Cincinnati would continue to be a thorn in Hulbert's side. While the league had a understood practice of disallowing Sunday baseball and serving alcohol at the parks, there was no official rule, and Cincinnati did both. At the end of the 1881 season, Hulbert had had enough. He put the rule in the rulebooks then made it retroactive to the 1881 season and banned Cincinnati from his league when they refused to apologise to him. Cincinnati would go on to form the influential American Association, but that's a story for another day.

Expelling Cincinnati would be Hulbert's final significant act in baseball - he died in April of 1882, leaving the White Stockings to Al Spalding. At the time, he was hailed as a hero to baseball, providing (and holding together) a new league as the NA suffered from moral ills. The

Chicago Tribune wrote: "There is not in America a player, club, officer or patron of the game who will not feel that the loss is irreparable," while his old nemesis Henry Chadwick gushed about his "invaluable service rendered ... in elevating [baseball's] moral tone, and in extirpating the evils which at one time threatened to ruin it." As time passed, however, Hulbert passed from the popular history of the sport, and by 1937 he was a footnote of history. In 1965 a third-grader from Barrington, IL wrote a letter to the

Chicago American writer Warren Brown asking how to get his great-great-uncle recognised by the baseball establishment. It took just another thirty years for Hulbert, unanimously voted at the time of his death by NL executives as the founder of the league, to be inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Ulimately, Hulbert's time as a baseball influencer was brief, chiefly from 1875-1882, but the single act he undertook, so incised at the Davy Force issue that he quit the NA to form the NL, shaped the course of baseball history in an obvious way; the NL would thrive from 1876 until today, a pillar fof baseball history and tradition in more than just name: the NL symbolised the shift toward professionalism, propriety, and the idea of baseball as the idyllic American sport. And it was the brainchild of William A Hulbert.

Previous:

1882 1/2 Ross Barnes

1880s Overview

Next:

1883 1/1 Frank Pidgeon