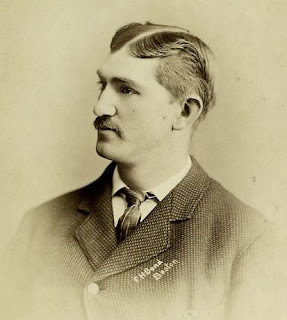

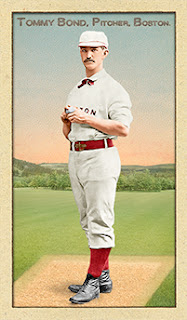

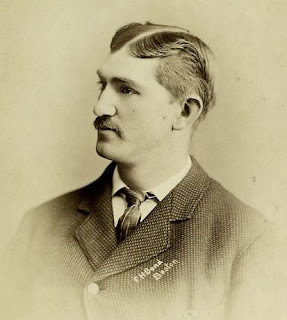

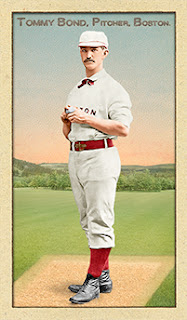

Thomas Henry Bond (1856-1941), Player

Eligible: 1885

Contributions: A control artist, Bond led the league three times in BB/9, finishing top ten in the league eight times. He was also a dominant power pitcher, leading baseball in strikeouts from 1874 to 1879 by a wide margin (614 to second-place 408). His resultant lifetime 5.04 lifetime K/BB would stand for 123 years, finally surpassed by Chris Sale in 2017. Baseball's best pitcher from the time of Spalding in the late National Association era until the early 1880s, retired with highest WAR of all time.

Tommy Bond was the successor in a long line of tricksters. Before the leagues became more established, the greatest pitcher in the land was the trickiest man in the box. Creighton hid an underhanded throwing, Spalding was a master of "headwork" - adjusting arc and speed, and Candy Cummings invented a whole new trick pitch, the curveball. Like his predecessors (including his mentor, Cummings) Bond pushed the rules to their limit, hiding a submarine-style low-sidearm action that was technically illegal to deliver the ball with previously-unseen accuracy and speed. Along the way he would carve a reputation as the best pitcher in the world.

Thomas Henry Bond was born in Granard, Ireland, in April 1856. Immigration records show the family settling into Brooklyn in 1862. Undoubtedly, Bond grew up playing ball on the neighbourhood streets and sandlots, but he first appears on a roster, the semi-pro Washington Nine, in 1873, aged 17. He would also play for one of the city's top semi-pro teams, the Brooklyn Athletics, that season. Bond appears to have been highly sought-after for the unprecedented velocity he could achieve with his nearly-sidearm (and thus nearly-illegal) delivery, and he had been invited to try out for the professional Brooklyn Atlantics of the National Association in 1872, but they couldn't find a catcher able to handle his velocity (remember the pitcher was only 45 feet away and there were no gloves yet).

After spending 1873 as a semi-pro, Bond debuted as a professional in 1874, still just 18, with the Brooklyn Atlantics, managed by NA veteran and amateur legend Bob Ferguson. Bond was the team's starting pitcher, which in 1874 meant he threw 497 of the team's 506 innings (Ferguson gave him one game off in June). Bond threw well, putting up a 2.03 ERA, good for a ERA+ of 101. He ranked as one of the better pitchers in the league by K/9 (4th) and BB/9 (1st), making a name for himself as the game's top control pitcher outside of possibly Al Spalding. As a result, Bond led his league in K/BB for the first of four times - as a teenager. The brightest moment of his rookie campaign came late in the year - on 20 October he held the New York Mutuals hitless for 8 2/3 innings, when Joe Start doubled. There wasn't even a word for what he'd lost yet - it would have been baseball's first no-hitter.

Before the 1875 season Ferguson signed on to manage and play for the Hartford Dark Blues. Ferguson asked his young pitcher to join him, and Bond obliged. Because the season would expand from 56 to 82 games, Hartford also signed Candy Cummings, possible inventor of the curveball, serial contract jumper, and in 1875 on the shortlist for #2 pitcher in the world outside of Spalding (George Zetlein and Dick McBride being the other two contenders). Cummings, aside from being the master of his tricky curveball, was also one of the game's best control artists, and was assigned the job of mentoring Bond. Bond played right field for most of the first half of the season, until Cummings began to wear down, at which point the two shared pitching duties. The rest did both men well - Cummings had a return to form and Bond broke out as a star, posting an ERA of 1.41 (167+) in 352 innings.

|

| The 1876 Hartford Dark Blues |

Bond took advantage of the opportunity, and when the Dark Blues fled the dissolving NA for William Hulbert's fledgling National League in 1876, Bond was Hartford's premier pitcher. He and Cummings had similar ability to control the ball, but Bond's largely-illegal underhanded throwing made him able to miss bats at an unprecedented rate (he was striking out almost two men a game). Bond threw another 408 innings while Cummings threw just 216. He put up a 1.68 ERA (143+) and led the league with a 1.96 FIP. His 6.77 K/BB was not only the first of three times he would lead the NL in K/BB, it set a record that would stand until 1880.

Bond's career took a turn partway through the 1876 season. In August he accused his manager, Ferguson, of throwing a match against Boston. Ferguson went to Hartford's president, Morgan Bulkely (then president of the NL as well), who demanded proof which Bond was unable to supply. Accused of defamation, he was suspended, and though Bond issued a public retraction Candy Cummings pitched the game's final 20 games. Boston took advantage of the situation and swooped in to sign the disgraced ace for the 1877 season.

At 20 years of age, Bond was established as the best pitcher in baseball, but his career record stood at just 72-61 as he played for second-class ballclubs. In joining Boston, Bond would have a crack at playing alongside some of the game's best: Jim ORourke, Deacon White, George Wright, and the legendary manager Harry Wright. The team went 42-18 and won the NL Pennant, Bond's first taste of success. He did his part, leading the league with 40 wins, a 2.11 ERA, and a 4.72 K/BB over 521 innings.

Bond kept up his success. Over the next two years he threw another 1088 innings for Boston, going 83-38 with a 2.01 ERA (122+). In two seasons, he put up 28.2 WAR, and he led Boston to the 1878 Pennant, his second.

This was essentially the height of power for Bond. Going into the 1880 season everything seemed to be going right. He turned 24 on April 2, and since 1874 he had been baseball's dominant pitcher. He was its best power pitcher and its best finesse pitcher, he had led the world (NA and NL) in WAR since 1874 and in all of baseball history (going back to 1871) was second only to Al Spalding. Bond had studied under the legendary Candy Cummings, won pennants, and led the league in every imaginable statistic along the way. But he'd also been throwing at the highest levels since he was a schoolboy, and at unimaginable volume: Before that 24th birthday he'd thrown nearly 3000 innings as a professional, and averaged 536 innings during his first three years in Boston. Nobody knew it yet, but Bond's arm was already shot.

Signs of shopwear were already present. Bond struggled early in the season and blamed it on his new catcher, rookie Phil Powers. Manager Harry Wright recognized the signs of fatigue and had young outfielder (and fellow Irishman) Curry Foley throw 238 innings, limiting Bond to *just* 493. His 49 complete games were the fewest since he split the 68-game 1876 schedule with Candy Cummings. He went 26-29 and his 2.67 ERA was good for just a 84 ERA+. Within six months of being regaled as the pitcher of his era, Bond was done.

Boston brought him back for the 1881 season to see what he had, but by then the NL had moved the pitcher's box back from 45 feet to 50, accommodating faster pitchers like Bond had once been. With nothing left, the greater distance proved too great a challenge, and after a 19-hit shellacking from Detroit Bond retired with a 0-3 record. The

Cincinnati Commercial Tribune crowed that "the fifty-foot rule has shelved Tommy Bond as a pitcher." Bond joined his brother in business in New York that summer, but returned to Boston, where the renowned Irish pitcher enjoyed great fame, by the fall.

The following March, 1882, Harvard's baseball team invited the local legend to work out with them, perhaps to hand down some sage wisdom to the young players. We don't know how much coaching Bond did that spring, but we do know that some of the baseball team's youth seemed to rub off on the veteran hurler. Tinkering with a new delivery, Bond, now 26, felt 'new life' in his arm, and was offered a contract by the NL's nearby Worcester Ruby Legs. Unfortunately, Bond still had nothing - he threw just 12 innings across two starts, walking seven men as his famous control dissolved at 50 feet. He insisted on sticking around the club, getting into six games as an outfielder, a role he sporadically filled during his career, despite his career .238 batting average. He even managed seven games, though he retired once again in June. Bond was connected to other clubs, but nothing came of it, though he did appear for the semi-pro Memphis Eckfords later in 1882. His retirement looked permanent. He stayed away from baseball in 1883, though he made a few appearances as an umpire in the Boston area following the abrupt resignation of umpire WE Furlong

In 1884 Bond was approached by Boston baseball heroes Harry Wright and Tim Murnane to join Boston's new Union Association club. By this time, baseball had removed most of the stern restrictions on deliveries, and pitchers were throwing much as they are today, and Bond found new speed and accuracy with a shoulder-level delivery. Now 28 years old Bond threw 189 decent innings for Boston, putting up a 3.00 ERA that was good for a 101 ERA+ and a 9.14 K/BB that was reminiscent of the younger Bond and one of the best in the fledgling major league. He also made his way into the outfield several times and ended up hitting an impressive .296 with eight doubles, in 162 ABs, one of the better hitters in the league.

Bond had a falling out with Boston in July and left the team, catching on with the Indianapolis Hoosiers of the American Association. He put up a 5.65 ERA in five games with his new team and retired for a third and final time, moving back to Boston for good. He spent the 1880s as a substitute umpire for several leagues and college circuits, even going 3-0 in sporadic appearances for a Brockton independent league team in 1886. He fathered three children with his wife Louise, whom he had met in his earlier Boston days and worked for her family business until taking a job with the Boston Assessor's office, which he worked for 35 years.

Louise passed away in 1933, and in 1936 Bond appeared publicly on a baseball diamond for the last time, still able to play catch with his old teammates at an old-timers game. Bond was 80. He would pass away in 1941 at his daughter's house in Boston, and was buried at Forest Hills.

Bond was a dreamer, and I would struggle to find another person who fought so hard to stay in a game that passed him by. By age 25 baseball was done with him, but Bond came back year after year with new mechanics, renewed optimism, under new rules, at a new position. He tried hitting, managing, even umpiring, jumping teams, leagues, even levels of professionalism. Anything to stay in the game. I'm reminded of the great essay by Bart Giamatti,

The Green Fields of the Mind:

It breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer ... and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall alone.

Tommy Bond was the best in the world at the most popular sport in his country for a number of years. He was truly great. Though he played at the very beginning of professional baseball, only 31 other pitchers have posted a higher JAWS score, and he still ranks 58th in bWAR. It must have crushed him to show up one day and not have anything left. Even when his arm was spent he kept coming back, willing himself into the game. "Hope springs eternal", Pope wrote, and baseball has always had a particular affiliation with that sentiment, and Tommy Bond embodied that as much as anybody to ever pick up a baseball.

Previous:

1884 2/2 Abraham Tucker

1880s Overview

Next:

1885 2/2 Charles DeBost